The Race against Time - Part 1

- Marleen Tigersee

- Jan 30, 2023

- 5 min read

Updated: May 31, 2025

It was dark and cold. So cold that no human being or animal should venture outside. And it was storming. Thousands and thousands of snowflakes swirled through the night and made progress almost impossible. Even with a dog sled and the right equipment. But Gunnar Kaasen had no choice on this February night but to embark on this dangerous journey, because it was a matter of life and death. The place is Alaska, the year is 1925 and the temperature is -55 degrees Celsius.

A few months earlier in the autumn of 1924, The inhabitants of the small town of Nome in Alaska were getting ready for winter. Enough supplies had to be stockpiled to last until spring, because until then, as every year, the town was cut off from the outside world due to the extreme weather conditions. Curtis Welch, the doctor at the only hospital in Nome, had also gone through his inventory to make sure he was well equipped for the next months. Back in the summer, he had noticed that he was out of fresh antitoxin, the antidote to the dreaded childhood disease diphtheria. Welch had then ordered a new batch, but it had never arrived. Now he could only hope that the drug would not be needed until next spring.

Man and dog

Life in Nome has always been tough. The farthest northwestern town in North America, two degrees south of the Arctic Circle, is known for temperatures well below -40 degrees Celsius and heavy snowstorms in the winter season. Nome was once a gold-mining town, with a population of 20,000 at its peak. But there was not much of that left in the 1920s. The cruel winters and the lack of gold discoveries eventually caused the population to shrink to 1400. A third of them were Inuit, who mostly lived in huts or tents a little outside the town. But there was something that united all people in these latitudes: the sled dogs.

The backbone of the dogs is the backbone of Alaska. (Will Rogers, American actor and author 1935)

Life without dogs - unthinkable in Alaska. The animals are perfectly adapted to the harsh climate, they are strong, persistent and hardy and able to pull sledges with heavy loads many kilometres over rough terrain. Their instincts are also second to none. They can sense dangerous spots on the ice and avoid them in time, which has already saved the lives of some mushers (that's what sled drivers are called in Alaska). The smartest and best dogs were always used as guide dogs and deep friendships often developed between them and their masters.

Suspected cases

When the last cargo ship had finally left and all of Nome was getting ready for winter, an Inuit family went to see Dr Welch. The two-year-old girl was very weak and refused to eat. When asked if she was suffering from a sore throat, the parents replied in the negative. The other siblings had no symptoms, so the doctor ruled out diphtheria, as this disease is highly contagious. Welch suspected another, less serious infectious disease and sent the family home, but the girl was dead the next day.

In late December, the doctor was called to an eight-year-old girl with an inflamed throat. As there had been numerous cases of tonsillitis in Nome a few months earlier, the girl received the same diagnosis from Welch. She too was not to live to see 1925.

The fact that Welch did not immediately recognise the deadly disease diphtheria had several reasons. His daily routine consisted of treating cuts and frostbite. The doctor had little experience with contagious infectious diseases. By the standards of the time, St. Maynard Hospital in Nome was considered the largest and most modern in the area, but the equipment was very basic. There was no laboratory or bacterial incubators, so Welch was forced to make his diagnoses only by external signs. In the early stages, diphtheria resembles a mostly harmless tonsillitis and the symptoms can vary greatly. However, purulent ulcers that form in the mouth and throat and smell unpleasant are very characteristic. These swell up so much that the patient suffocates in agony.

When Welch was called to a seriously ill Inuit boy on the morning of 21 January, who showed all the known symptoms of diphtheria, there was no longer any doubt: the state of emergency had to be declared.

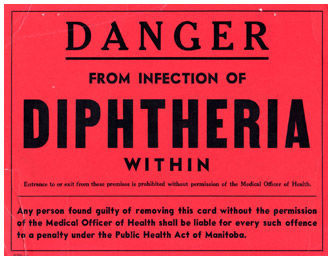

Quarantine

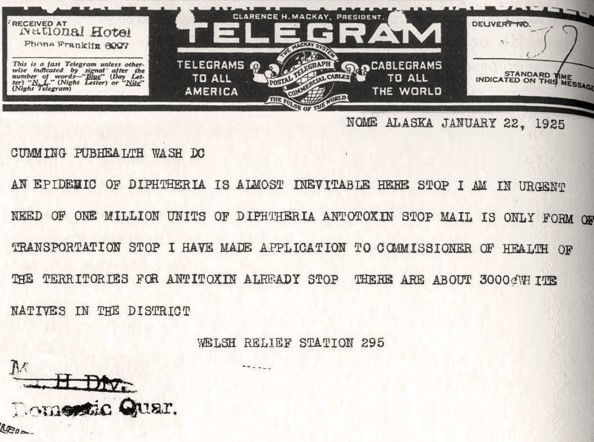

The mayor, whom Welch had informed right after his visit, called the city council together. An immediate quarantine and curfew was imposed on the city. Next, probably the most important question had to be resolved: Where and how quickly could the saving antitoxin be procured? Since the harbour was already frozen, there were only two options, by plane or by dog sled. The faster option was certainly the plane, but there were some difficulties. Aviation in Alaska was still in its infancy in the 1920s, engines often failed in the extreme temperatures, reliable de-icing agents did not yet exist, and the cockpit was open, leaving the pilots unprotected against the elements at -40 degrees Celsius.* If a plane crashed, the serum would be lost. In the end, it was decided to take the longer but safer route overland by dog sled. Telegrams were sent to all the important official agencies requesting immediate delivery of fresh antitoxin.

When the promise came a short time later, a plan was made. The package with the serum was to be sent by train to the nearest railway station in Nenana. From there, a distance of over 1,000 kilometres to Nome had to be covered by sledge. But who was to make the long, dangerous journey? The search for the best mushers in the area could begin...

... TO BE CONTINUED ...

*The following items of clothing were worn by pilot and explorer Carl Ben Eielson during his flights in Alaska: [...] two pairs of heavy wool socks, one pair of socks of caribou fur, one pair of moccasin boots reaching above the knees, one set of thick underwear, one pair of khaki trousers, one pair of thick Hudson Bay wool trousers, one thick shirt, one jumper, one cap of marten fur, one pair of goggles, and over all a parka of reindeer fur reaching above the knees, and a hood trimmed with wolf fur. (The Cruelest Miles. The Heroic Story of Dogs and Men in a Race against an Epedemic, p. 147-148)

Comments